Choosing the five best CPUs among Intel’s offerings can be challenging.

Throughout its decades-long history, Intel has always been at the forefront of computing with its CPUs, often topping our lists of best gaming CPUs and best workstation CPUs.

Choosing Intel’s five best CPUs is a bit challenging, as Intel has historically come in at number one, which raises the bar for Intel CPUs. Taking into account performance, value, innovation, and historical reputation, here’s a narrowing down of what we think is Chipzilla’s best processors since the company’s inception. This is by no means an exhaustive list, as it’s inevitable that some great CPUs were inadvertently skipped.

01

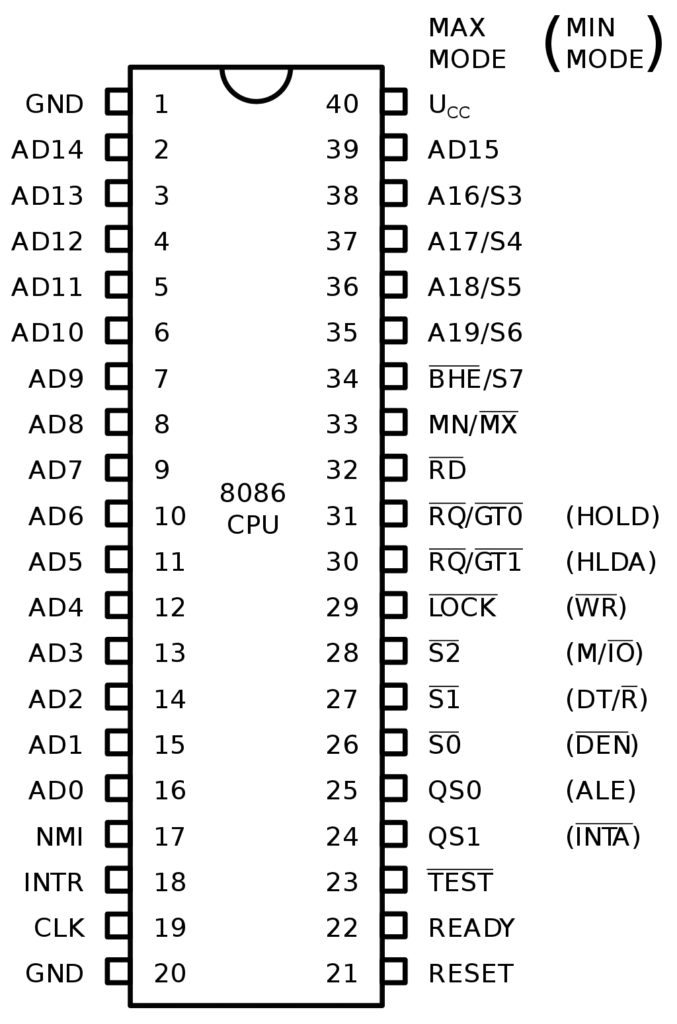

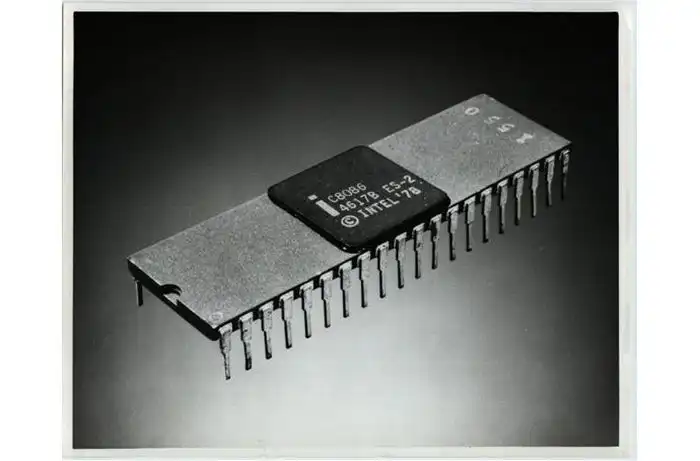

Fifth place: Intel 8086

Founded in 1968, Intel was a pioneer in the emerging semiconductor industry. It started as a memory designer and manufacturer but eventually began developing CPUs in the 1970s. the CPU business was more promising for the company because there were few competitors and it was easy to achieve world firsts, such as the Intel 4004, which Intel claimed was “the first general-purpose microprocessor,” meaning it was not specialized like other processors. For example, the Intel 4004, which Intel claimed was “the first general-purpose microprocessor,” meaning that it was not specially designed like other processors.

With only 4 bits, the 4004 had a lot of room for improvement, and in 1978, Intel introduced the first 16-bit CPU, the Intel 8086.

Although Intel claimed this was the world’s first 16-bit CPU, it wasn’t, and in fact, Intel was playing catch-up with companies like Texas Instruments, which had introduced 16-bit chips earlier. Motorola’s 68000 and Zilog’s Z8000 also hit the market the year after, generating further buzz.

Intel believed it could compete with the 8086, but it needed to convince the market to use it. Then-President and COO Andy Grove, Intel’s third employee and later CEO, launched a massive campaign called Operation Crush in 1980. According to author Nilakantasrinivasan J, “More than 1,000 employees were involved, working on committees, seminars, technical articles, new sales aids, and a new sales incentive program.” Two million dollars was set aside for advertising alone, declaring that “the age of the 8086 has arrived”.

| Model No. | Frequency | Technology | Temperature Rage | Package | Date of Release | Price (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8086 | 5 MHz | HMOS | 0 °C to 70 °C | June 8, 1978 | $86.65 | |

| 8086-1 | 10 MHz | HMOS II | Commercial | |||

| 8086-2 | 8 MHz | HMOS II | Commercial | January/February 1980 | $200 | |

| 8086-4 | 4 MHz | HMOS | Commercial | $72.50 | ||

| I8086 | 5 MHz | HMOS | Industrial −40 °C to +85 °C | May/June 1980 | $173.25 | |

| M8086 | 5 MHz | HMOS | Military-grade −55 °C to +125 °C | |||

| 80C86 | CMOS | 44 Pin |

The 8086 changed the company, and Intel sold its memory business in 1986 to focus entirely on CPUs. 8086 had 85% of the 16-bit processor market. This made the 8086’s x86 architecture forever relevant and still used in PCs and servers today, making Intel’s marketing statements almost prophetic.

The huge success of the 8086 caught the attention of IBM, which asked Intel to make a cheaper version for use in its upcoming personal computers, and Intel introduced a lite version of the 8088, which was 8-bit instead of 16-bit. In any case, the 8088-based personal computer (or PC, as it came to be known) was a huge success and easily won Intel’s Best Design Award for the 8086.

Incidentally, IBM was concerned that Intel didn’t have enough 8088 chips for the PC and asked Intel to find a partner to make more. Intel eventually chose another company founded in 1968 that also made memory and CPUs: Advanced Micro Devices, or AMD. Although Intel was a partner in the 80s, it eventually tried to exclude AMD in the 90s, which led to AMD winning the rights to the x86 architecture, creating a strong competitor.

02

Fourth Place: Core i5 2500K

Essentials

Product Collection: Legacy Intel® Core™ Processors

Code Name: Products formerly Sandy Bridge

Vertical Segment: Desktop

Processor Number: i5-2500K

Lithography: 32 nm

CPU Specifications

Total Cores: 4

Total Threads: 4

Max Turbo Frequency: 3.70 GHz

Intel® Turbo Boost Technology 2.0 Frequency: 3.70 GHz

Processor Base Frequency: 3.30 GHz

Cache: 6 MB Intel® Smart Cache

Bus Speed: 5 GT/s

TDP: 95 W

It didn’t take long for AMD to become a thorn in Intel’s side. most of the 2000s were truly painful for Intel as its NetBurst and Itanium architectures were strangled by Athlon and Opteron. However, it didn’t take long for Intel to regain the upper hand with its Core 2 CPUs, both technically and in terms of marketing dollars of dubious legitimacy. By the end of the 2010s, AMD was at a disadvantage and Intel was gaining momentum.

For the next generation, Intel was the first to introduce new second-generation CPUs with the new Sandy Bridge architecture in January 2011. Compared to the first generation, these CPUs weren’t exactly revolutionary, as they were still capped at four cores for mainstream desktops and featured only minor updates to Intel’s Turbo Boost technology. Still, there are some key upgrades: 32nm nodes (although some first-generation CPUs also use 32nm), higher IPC of around 10%, and fast synchronous video encoding.

Perhaps the most striking innovation of Sandy Bridge is the unification of the CPU chip with the integrated graphics and memory controller chips. While Intel and AMD have gone back to putting graphics chips on separate chips in some processors, combining the two pieces of silicon into one was a big step forward at the time, especially for memory controllers.

Rather than a massive upgrade in any particular category, we find that Sandy Bridge offers a variety of improvements across the board; it’s much faster and more energy efficient than the first generation and features fast synchronization that not even AMD or Nvidia has a solution for. The quad-core Core i5-2500K in particular is a great CPU thanks to its $216 price tag, compared to the $317 Core i7-2600K, which also has only four cores.

While second-generation Core hasn’t exactly reshaped the CPU landscape, there’s a much bigger mountain to climb now if AMD wants to stand a chance, and AMD didn’t respond until October, almost a year after they undoubtedly looked bad both at the time and in hindsight. While AMD’s eight-core high-end FX-8150 is (somewhat) only a bit more expensive than the 2500K, we think the 2500K is still the better chip.

Despite AMD’s poor performance on Bulldozer, few predicted that this would effectively mark AMD’s exit from the high-performance CPU market, even for the mainstream. Intel was then rewarded over the next five years.

03

Third Place: Core i7 920

Essentials

Product Collection: Legacy Intel® Core™ Processors

Code Name: Products formerly Bloomfield

Vertical Segment: Desktop

Processor Number: i7-920

Lithography: 45 nm

CPU Specifications

Total Cores: 4

Total Threads: 8

Max Turbo Frequency: 2.93 GHz

Processor Base Frequency: 2.66 GHz

Cache: 8 MB Intel® Smart Cache

Bus Speed: 4.8 GT/s

# of QPI Link: 1

TDP: 130 W

Although the Core 2 has put Intel firmly in the number-one spot for the first time in years, the company’s position is not entirely secure. After all, the Core architecture wasn’t carefully planned and executed as Intel rushed to replace its NetBurst-based Pentium 4 line with a truly competitive product. Core 2 held the lead even after AMD introduced its new Phenom line in 2007, but if Intel wanted to stay ahead and continue to sell, it would need a new line of CPUs.

Of all its shortcomings, two in particular need to be addressed. First, the Core 2 quad-core CPU was made from two dual-core chips because the original Core architecture was based on the mobile Pentium M chip and thus was not designed with quad-core in mind. Additionally, Intel had to abandon Hyper-Threading technology, which provided two threads per core instead of one, again because the Pentium M didn’t have that feature, while later Pentium 4 CPUs did.

With the introduction of the new Nehalem architecture in 2008, Intel finally had a true quad-core CPU with Hyper-Threading and added a third level of cache and clock acceleration. Architecturally, it’s very similar to what AMD did with its K10-based Phenom CPUs, but with a much more refined execution. Nehalem’s more advanced 45nm node is also a nice plus.

Intel’s next-generation Nehalem processors ushered in the Core I era with three Core i7 CPUs, with the Core i7-920 being the obvious mainstream choice, priced at $284. Although clocked at just 2.66GHz, well below the $399 i7-965 Extreme at 3.2GHz, the i7-920 is so powerful that it beat even the fastest Core 2 Extreme in almost every benchmark we reviewed, often by a significant margin.

Intel is making a comeback with Core, and with first-generation CPUs, that comeback is bound to continue. From flagship to flagship, Intel’s Core i7-965 Extreme is 64% faster than AMD’s Phenom X4 9950 Black Edition. Considering that Phenom beat Intel by building four cores on a single piece of silicon and implementing an L3 cache, this could sting AMD. Even the six-core Phenom II CPUs are no match for AMD, which is no longer the Pentium-killing company it once was.

Intel doesn’t just offer quad-core CPUs, however, but also a much larger number of cores. Initially, these were six- and eight-core models limited to Xeon servers, which used two quad-core chips and were essentially Core 2 duplicates. However, once Intel shrunk Nehalem to 32nm, it created true six-core chips and even a ten-core CPU, a world first. Intel may be ahead of AMD more than ever, and the gap will continue to widen over the next eight years.

04

Second Place: Core i9 13900K

Essentials

Product Collection: 13th Generation Intel® Core™ i9 Processors

Code Name: Products formerly Raptor Lake

Vertical Segment: Desktop

Processor Number: i9-13900K

Lithography: Intel 7

Recommended Customer Price: $589-$599

Use Conditions: PC/Client/Tablet, Workstation

CPU Specifications

Total Cores: 24

Total Threads: 8

Max Turbo Frequency: 5.80 GHz

Processor Base Frequency: 2.66 GHz

Cache: 36 MB Intel® Smart Cache

Bus Speed: 4.8 GT/s

Processor Base Power: 125 W

In the decade since the launch of the second generation of Sandy Bridge-based CPUs, Intel has struggled to match its past.

At first, this was because Intel had no incentive to compete. After all, AMD had essentially withdrawn from the market, but by the time AMD made a comeback in 2017 with Ryzen, it was already too late for Intel. The company’s 10nm node was repeatedly delayed for years, and Intel’s dominance continued to slip until it ranked second in many categories in 2019. It wasn’t until 2021, with the launch of 12th-generation Alder Lake CPUs, that 10nm became truly viable.

While Alder Lake easily beat the Ryzen 5000, it did so a year after the Ryzen 5000 was released, meaning AMD’s next generation was already here. This puts Intel in a difficult position, as its 7nm/Intel 4 CPUs are far from complete. In any case, they rely on a lot of cutting-edge and novel technologies, and launching them in front of AMD’s tried-and-true Ryzen chips is risky. Intel doesn’t want to be late or fail again, but the two seem to be mutually exclusive.

But over the past few years, as AMD has continued to win, Intel has learned two important lessons: dramatically increasing the number of cores in a generation is a winning strategy, and increasing the amount of cache is great for gaming performance. Intel already has a great CPU on its hands, making a version with more cores and cache won’t take long, and it could potentially compete with AMD’s next generation (though it would undoubtedly increase power consumption).

The 2022 CPU showdown begins with the September release of the Ryzen 7000, AMD’s new flagship Ryzen 9 7950X, which is much faster than the Ryzen 9 5950X and Core i9-12900K. This isn’t surprising as AMD has switched to TSMC’s state-of-the-art 5nm node, which has seen a significant increase in power consumption, and has also gained some additional IPC. Whether or not the 13th generation Raptor Lake CPUs will be able to reach the attack distance is up in the air as the only major upgrade to the Core i9-13900K is an additional 8 E-cores rather than more P-cores, which are faster, the L2 and L3 also more cache and higher clock speeds.

Despite all the problems on paper, the Core i9-13900K proved to be as fast as the 7950X when it launched in November. In our review, the 13900K trailed only the 7950X in productivity workloads and beat the 7950X in gaming by a sizable margin. Intel’s ability to match AMD’s performance is impressive on its own, but the 13th Gen beats AMD on price as well. The CPU itself is quite cheap, and with discounted LGA 1700 600 series motherboards The CPUs themselves are quite cheap, and with discounted LGA 1700 600-series motherboards and DDR4 RAM, you can build a 13th-gen PC very cheaply.

Meanwhile, the Ryzen 7000 CPUs were relatively expensive for the level of performance they offered, didn’t cover the lower end of the market (and still don’t to this day), and required expensive new AM5 600-series motherboards and DDR5 RAM, which cost a lot more than DDR4. The two selling points of the Ryzen 7000 were efficiency and longer upgrade paths, which were important, but not the most important.

While the 13th generation has technically been replaced by the 14th, both use the Raptor Lake architecture and are often the better choice since the 13th generation is cheaper.AMD has since addressed some of the pricing issues with the Ryzen 7000 and AM5 motherboards, but the Ryzen 7000 is still generally more expensive. Both companies plan to release new architectures and CPUs later in 2024, which will be the end of the generation.

05

First Place: Core 2 Quad Q6600

Essentials

Product Collection: Legacy® Core™ i9 Processors

Code Name: Products formerly Kentsfield

Vertical Segment: Desktop

Processor Number: Q6600

Lithography: 65 nm

New Design Availability Expiration Date: Sunday, January 8, 2012

CPU Specifications

Total Cores: 4

Processor Base Frequency: 2.40 GHz

Cache: 8 MB L2 Cache

Bus Speed: 1066 MHz

FSB Parity: No

TDP: 125 W

VID Voltage Range: 0.8500V-1.500V

The early to mid-2000s were tough times for Intel. In the PC business, the NetBurst-based Pentium 4 was a disaster because of its high power consumption and inability to successfully achieve the high clock frequencies Intel needed, leading to the cancellation of the 4GHz Pentium 4 and subsequent CPU Tejas. The lucrative server business was arguably worse, as Intel had invested billions of dollars in Anthem, which was incompatible with the x86 software ecosystem that Intel itself had cultivated. When AMD introduced Opteron with a 64-bit version of its x86 architecture, the era of Anthem was over.

To keep the market in its favor, Intel spent billions of dollars in marketing to Dell, HP, and other OEMs to keep them from using AMD, which generated fees and fines for Chipzilla worldwide. It’s not a sustainable strategy (and obviously of questionable legality), and since NetBurst and Itanium are both dead ends, Intel needs a new architecture, and fast.

Luckily for Intel, it did have another architecture to work with; Intel’s Haifa team worked on the 2003 Pentium M series of laptops. Fortunately for Intel, the Pentium M was based primarily on the Pentium III rather than the Pentium 4, which meant it was much more efficient. However, because it was designed for laptops, Intel had to do some work to make it suitable for desktops and servers. Most notably, Intel made Core 64-bit and kept the x86 architecture, just as AMD did with the Athlon 64. In addition to these technical changes, Intel also made a name change to the architecture, renaming it Core.

Technically, Core was introduced in early 2006 as a laptop-only line but was quickly replaced in just a few months by Core 2 for laptops and desktops. In effect, Core 2 is a downgraded version. The original Conroe-based Core 2 Duo CPUs had lower mainframe frequencies, less L2 cache, and even dropped the cutting-edge Hyper-Threading feature. Nonetheless, the Core 2’s higher IPC proved to be a killer in our Core 2 Duo reviews, with even the slowest E6600s almost always beating the faster Pentium 4 and Athlon 64 CPUs.

Intel had bigger performance ambitions, however, and introduced the quad-core Core 2 Quad CPU in January 2007. the Core was designed for just two cores, so to make the first-ever quad-core CPU, Intel simply put two dual-core chips together in the same package. the Q6600 was the first quad-core desktop CPU you could buy, even though it was initially launched at an eye-watering price. The Q6600 was the first quad-core desktop CPU you could buy, and while it initially launched at a jaw-dropping $851, by August the price had dropped to just $266. Its high performance and then relatively low price made it one of Intel’s most popular CPUs ever.

Intel’s discarded quad-core processor completely preempted AMD’s upcoming Phenom CPU, which had a quad-core CPU that didn’t need to rely on a multi-chip solution. however, when the Phenom was launched, it was clear that Intel’s jankier chip design was better. In our review, the Phenom 9700 was nearly 13 percent slower than the Q6600, not to mention all the other faster quad-core processors Intel has introduced. Even the 2009 quad-core Phenom II X4 struggled to beat the Q6600, which is based on 2006 technology.

Despite all the paper problems, Core 2 is still legendary: the original architecture was never designed for desktops and servers, it could only run two cores on a single chip, and it got rid of hyperthreading. It’s almost certain that neither the Phenom nor the Phenom II could beat Intel’s CPUs, and there’s no denying that Intel dominated in this regard, securing the company’s number-one position, which lasted for about 13 years until the arrival of the Ryzen 3000.

06

Honorable Mention: Alder Lake

Just as Intel nearly died in the 2000s by trying to build a 10GHz Pentium 4, Intel’s mess in the late 2010s and early 2020s nearly died because it tried to compress nearly a decade of process advances into just a few years. Intel’s 10nm node was a disaster: it missed its original 2015 release date, got to 2018, which was bad enough, and then powered laptop-specific Ice Lake and Tiger Lake CPUs from 2019 to 2021.

In contrast, AMD triumphed in 2019 and 2020. the Ryzen 3000 beat Intel’s 9th gen lineup, the Ryzen 4000 made Intel’s mobile CPUs obsolete, and the Ryzen 5000 easily beat Intel’s 10th gen offerings in gaming, taking away the last of Chipzilla’s topics. Why it’s the best CPU.

With the Ryzen 5000, AMD introduced a price hike, with its cheapest CPU, the Ryzen 5 5600X, starting at $300. Sure, these new chips are fast, but they don’t have the value advantage of AMD’s classics, and if you don’t have $300 to spare, you can’t even upgrade.

Thankfully, Intel is finally making a concerted effort in 2021 with the 12th generation of Alder Lake CPUs, which feature a new hybrid CPU lineup with two types of cores, a new architecture, a working 10nm node, PCIe 5.0 support, and compatibility with DDR4 and DDR5. The flagship Core i9-12900K has a total of 16 cores, on par with AMD’s Ryzen 9 5950X. In our review, the 12900K won clear victories in multi-core and single-core apps, and narrowly won in gaming. the 12900K is also priced at just $589, compared to the $799 price tag of the 5950X, making the 12900K the clear winner.

Incredibly, though, AMD hasn’t updated the Ryzen 5000 series since its launch in late 2020; that means the cheapest CPU is still $300. By contrast, Intel plans to launch a range of budget options, such as the Core i5-12400, in January 2022.AMD has responded by cutting back on chips with mediocre performance and value, a shocking failure for a company that was once the king of value.

Of course, the Alder Lake generation was a year late, and AMD eventually introduced better-value models, lowered the price, and released the cutting-edge Ryzen 7 5800X3D with 3D V-Cache. With that in mind, it’s hard to see the 12th generation making it onto the list, especially since the 13th generation proved that Alder Lake could do so much more. What’s even more surprising is that Intel is competitive with a node that was originally scheduled to launch in 2015. If Intel hadn’t tried to pack nearly a decade’s worth of improvements into about two years of development and instead spread those advances over multiple generations, Chipzilla might have remained Chipzilla, and not just the name.

Disclaimer:

- This channel does not make any representations or warranties regarding the availability, accuracy, timeliness, effectiveness, or completeness of any information posted. It hereby disclaims any liability or consequences arising from the use of the information.

- This channel is non-commercial and non-profit. The re-posted content does not signify endorsement of its views or responsibility for its authenticity. It does not intend to constitute any other guidance. This channel is not liable for any inaccuracies or errors in the re-posted or published information, directly or indirectly.

- Some data, materials, text, images, etc., used in this channel are sourced from the internet, and all reposts are duly credited to their sources. If you discover any work that infringes on your intellectual property rights or personal legal interests, please contact us, and we will promptly modify or remove it.