Avoid the self-fulfilling prophecy trap.

As August approaches, the internal debate on US semiconductor policy towards China intensifies, as a new sanction plan is set to be released between July and August. On the one hand, US chip giants (From Intel to IDM: Reshaping the Semiconductor Industry) are attempting to hinder harsher sanctions against China, while on the other hand, agencies like the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) and the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) strive to enforce more stringent measures. BIS mainly handled national security and high-tech issues and was responsible for the sanction plan against China’s advanced processes and AI on October 7th last year, while USTR is the department monitoring trade targets. With pressure from both within and outside the system and the upcoming elections next year, can US companies withstand the new offensive and prevent a worse situation from arising?

“War” Drummer

In recent days, The New York Times published a lengthy article titled “This Is an ‘Act of War’: Decoding the U.S. Chip Blockade Against China” (referred to as “Decoding” below). The title of the article is startling, and its content is sensational, presenting a robust call for a tough stance against China. It has reportedly sparked widespread sharing and discussion on social media in the United States, and prominent think tanks like RAND have praised it. Notably, Jack Warner, co-founder of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, which serves the U.S. political sphere, commented that this is the best report he has read on the chip blockade against China, as it delves into the essence of the problem from a technological perspective: the United States is telling China to either accept failure or go to war.

This article has also been disseminated by foreign media to China, causing strong reactions and saturating the internet with debates about the China-U.S. chip war. It has generated two main viewpoints: first, the most severe sanctions are imminent; second, a firm response should be employed against toughness. While it may be forgivable for outside media to indulge in imaginative interpretations, if the industry falls into the traps set by organizations like BIS, it becomes concerning.

The New York Times piece, rather than being a genuine interview or report, appears to be a promotional piece for BIS, with ALEX W. PALMER as the author. Palmer, a writer who previously studied at Peking University and has a long-standing interest in Chinese topics, has covered a wide range of fields. One of his most influential articles was a lengthy piece published in GQ titled “The Great Art Heist of China,” which was later turned into a movie and sparked significant animosity in the art world, both in China and abroad. Recently, he wrote an article titled “TikTok’s Success and Destiny: A Product of the Era Caught Between China and the United States,” and now he ventures into the semiconductor domain, seemingly treating the subject lightly but skillfully weaving the narrative.

“Decoding” is a piece that resembles a sandwich, starting and ending with interviews with BIS while its main content is lifted from the extensive report by the think tank CSIS titled “A New Strategy for China’s Microchip Technology War” (referred to as “Strategy” below), which serves as the foundation for the article’s professionalism. The author cleverly uses the voice of the “Strategy” report’s authors to convey its contents, completing the adaptation work. The title “war” is derived from the opening section of the report, and many notable phrases, such as “The Trump administration targeted companies, the Biden administration targets the entire industry,” and “We will not only prevent China (Unlocking China’s Semiconductor Merger Challenges) from making any progress in technology, but we will also actively reverse their current technological level,” are all drawn from the “Strategy” report.

However, “Decoding” and “Strategy” present completely opposing core viewpoints. While “Strategy” believes that the framework of U.S. sanctions against China has been effectively established, creating a significant security gap between the two countries, “Decoding,” on the other hand, voices deep concerns through the perspective of BIS that China’s semiconductor industry may break through the blockade. The article expresses doubt about whether BIS can effectively counter the entire Chinese government, questioning how its actions can keep up with China’s speed and financial investment in chip development, stating, “Our goal is to stop as much as we can.”

The author’s worry about China’s ability to bypass sanctions serves the purpose of seeking more funding for BIS. The article’s opening is unambiguous: “BIS is small, one of the 13 bureaus of the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the smallest federal agency in terms of budget: slightly over $140 million in the 2022 budget, about one-eighth the cost of a Patriot air defense missile. The bureau employs about 350 agents and officials who collectively monitor trillions of dollars worth of transactions taking place worldwide.”

Thus, the intentions of BIS and “Decoding” become clear—they aim to fuel collective panic, mobilize the United States to impose stricter sanctions on China, and escalate the China-U.S. semiconductor rivalry into a war rather than competition. The more intense the conflict, the more China will be surveilled, leading to increased financial allocations for BIS. Some American elites prefer to label the China-U.S. semiconductor competition as a war, as evident in the recent best-selling book by a historian titled “Chip War,” which has turned the author into a prominent figure in semiconductor-related congressional hearings and media interviews.

This manipulation of public opinion also has a strong intent to influence Chinese sentiment. The more overt and sensational it is, the more likely it will provoke a reaction from the Chinese public, and this has become a reality. At this juncture, if China were to falter and trigger an actual chip “war” proactively, it would play right into the hands of the U.S. decoupling proponents. Applying pressure to the adversary and enticing them into a strategic response from the opposing side, falling into the trap of “self-fulfilling prophecy,” is a tactic that the United States has frequently employed.

The Balancing of ‘Allies’

Fortunately, the world is not as submissive as the U.S. decoupling proponents would hope. Last year, Chip4 pointed out in their analysis of the chip bill that the United States’ ultimate weapon in sanctioning China is Chip4, and it can only achieve the goal of blocking China by mobilizing the entire Western supply chain system. The article “Strategy” also highlighted that the key to the U.S. blocking China lies in the degree of cooperation from its “allies,” as complete sanctions cannot be decided solely by the will of the United States. “The United States’ unilateral actions are a diplomatic gamble. Despite having control over many key elements in the global semiconductor supply chain, countries like Japan and the Netherlands also hold dominant positions in certain crucial sectors. If these countries continue to sell products to China as they did before, the effectiveness of the October 7th controls would be rendered ineffective.”

Because of the existence of “allies,” the U.S. sanctions can be implemented, but also due to the presence of “allies,” the U.S. cannot launch an all-out chip “war” without considering the losses it would incur.

Around the time when the October 7th sanctions were introduced, President Biden invested significant efforts in forming a unified front to sanction China, with even Japan only recently finalizing its sanction details. The reason for the passivity of “allies” is simple: the United States pays a huge price but gains the ability to target its only competitor, resulting in a considerable net gain. On the other hand, countries in Europe, Japan, South Korea, and others paid substantial costs, with little to no significant gains, and in turn, it significantly strengthened the United States’ suction power over global manufacturing. As long as the cost of continuing to displease “allies” remains relatively low, they may reluctantly continue to follow suit. However, if the pain becomes too intense and the losses too significant, they would naturally be unwilling to follow the U.S. lead.

Considering the efforts President Biden made in pushing forward the October 7th sanctions, the current level of sanctions is already the limit for “allies,” and it largely determines the maximum extent of U.S. sanctions against China. This leaves considerable space for China to continue participating in the global semiconductor (Semiconductor Testing Equipment Unveiled: Types and Impact) market, which is also a significant reason why Biden must emphasize that China and the U.S. are still in competition rather than engaged in a “cold war.”

Therefore, the complexity of the China-U.S. semiconductor relationship cannot be simply defined as either a war or competition. War implies the complete termination of cooperation, with both sides fighting for survival relentlessly. Competition, on the other hand, entails fair competition on a stage with established rules, where mutual benefits can be achieved. Currently, the China-U.S. semiconductor dynamic involves both sanctions and prohibitions, as well as trade and cooperation. It cannot be naively viewed as competition, nor can it be seen as a war as some U.S. hawks might hope. Sliding into a genuine chip war would be the worst outcome for China, with many aspects coming to a halt. The U.S. decoupling proponents, on the other hand, desire this outcome, as the cost for the U.S. semiconductor industry is relatively low, and a significant portion of politicians is willing to bear that cost.

The Struggle Between Businesses and Politicians

Under the current circumstances, for the United States to implement more stringent sanctions, it can only do so in specific areas where it has independent capabilities, such as the chip design sector where the U.S. holds an absolute advantage.

Both “Strategy” and “Decoding” acknowledge that restricting China’s domestic advanced semiconductor manufacturing has achieved its objectives, but there is no way to control private transactions of certain specific chips. Since it is not feasible to completely restrict the flow of chips into China, is there still a need for prohibitions on U.S. companies doing business with Chinese enterprises? This is why AI chips have become a focal point of U.S. sanction policies and a crucial aspect of lobbying efforts by the three major chip design giants to influence the U.S. government.

Both articles share a story about smuggling—recently, Chinese customs uncovered a case of smuggling AI chips disguised as pregnant women. China’s development of large-scale AI models heavily relies on advanced AI chips, and due to the sanctions, meeting this demand can only be accomplished through smuggling.

However, the focus of the two articles is completely different. According to “Decoding,” BIS has only three agents in China responsible for monitoring such physical transactions, and they are fundamentally incapable of supervising the smuggling of AI chips, causing concern for BIS. On the other hand, “Strategy” argues that the U.S. need not worry about AI chip smuggling since training on the scale of OpenAI requires tens of thousands of chips to achieve the necessary computing power, and the smuggling of small quantities cannot meet this level of demand.

Two interpretations, two directions: one suggests that the sanction framework still has loopholes that need to be addressed and require increased enforcement efforts, while the other asserts that the sanction framework has already been effective enough to limit China’s development of new technologies. Reality seems to confirm the latter perspective; shortly after the October 7th ban was introduced, OpenAI experienced significant growth, prompting numerous domestic companies to announce plans for large-scale computing models, leading to a domestic rush to purchase advanced GPUs. Although there might be a long-term shortage of AI chips in China, soon after, scattered AI chips started appearing in Huaqiangbei, unable to be sold. This is precise as “Strategy” pointed out—small-scale shipments cannot fulfill the needs of large companies, resulting in sporadic inventory.

This policy of restricting chip sales is facing strong opposition from U.S. companies. Only China has an AI chip market comparable to the United States, and with Chinese tech giants having immense demand but no access to purchases, how can U.S. design firms not be concerned? According to reports from foreign media, Intel CEO Bob Swan expressed during lobbying efforts with the U.S. government that the necessity of projects like building factories in Ohio would significantly decrease without orders from Chinese customers. Jensen Huang also stated that the Chinese market is irreplaceable, and exiting the Chinese market is not a viable option. Colette Kress, the CFO of NVIDIA, believes that restricting AI chip exports to China “will permanently deprive the U.S. industry of opportunities.”

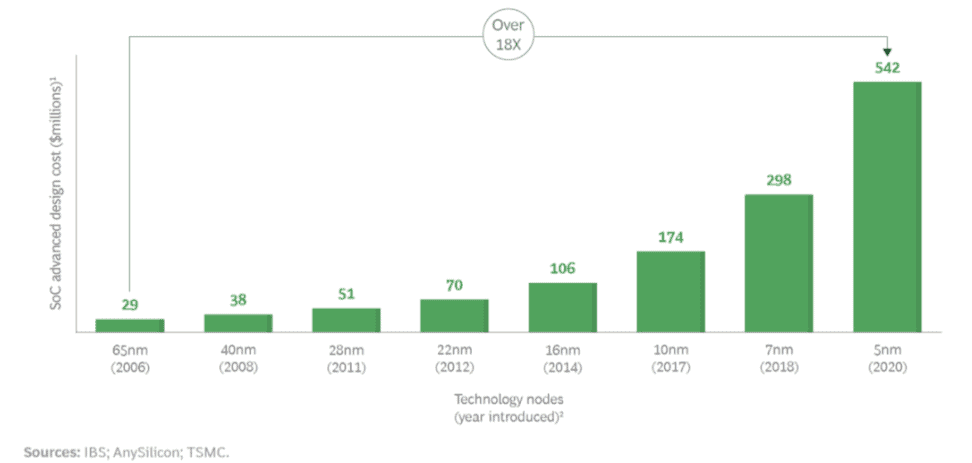

A report by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) provides data to support this claim: U.S. chip design revenues are declining, with global market share dropping from over 50% in 2015 to 46% in 2020. If the current trend continues, it may further decrease to 36% by 2030. This is attributed to the increasing complexity of chips, leading to a substantial rise in development costs, especially in advanced processes.

In fact, there are significant divisions within the U.S. government regarding its approach to sanctions. The key point of disagreement lies in whether there is a need to further escalate the sanctions when the current framework is already showing limited but effective results. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan acknowledged at the Aspen Security Forum that the approach of creating a “small yard, high fence” has demonstrated some effectiveness.

CSIS believes that the 10·7 sanctions, which restrict devices at 14nm and below, are sufficient to ensure the security of the U.S. semiconductor industry for a considerable period. Even if China procures advanced chips for high-end manufacturing, the related industries remain highly dependent on the global supply chain. Unless China achieves complete self-sufficiency in the entire industry, a feat described in “Strategy” as akin to replicating all of human civilization, the industry’s dependence on the global supply chain will persist.

As a result, there are internal reflections within the U.S., such as Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen advocating for targeted sanctions against China and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo expressing disagreement with the idea of starting a technology war with China, instead emphasizing a more challenging competitive approach.

Of course, there are also hawks like U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai, who argue that pursuing efficiency and low-cost trade liberalization has led to fragile and high-risk supply chains and unsustainable globalization. They propose establishing more rules that prioritize U.S. needs and reversing the trend of competitive bottom-scraping.

Even so, those like Tai must still align their narratives with President Biden’s assertion that China and the U.S. are in a “competitive relationship.” It is foreseeable that under the pressure from the hawks and the upcoming U.S. presidential election next year, there may be new calls for sanctions. However, after the initial hawkish demands for sanctions have been sufficiently released, new sanction proposals will face significant resistance. Regardless of the eventual outcome, it is unlikely to break the current framework of “limited but effective” sanctions.

Conclusion

Clearly, the United States lacks the capacity to initiate a complete and decisive “war” due to two primary reasons: Firstly, “allies” are unwilling to continue harming their own interests, which is a decisive force shaping the framework of the sanction policy. Secondly, the opposition from U.S. chip companies determines the details of the sanctions. These two factors together form the “foundation” of the sanction policy. However, if China were to proactively initiate a confrontational chip “war,” it would be effortless, as long as we follow the tone of a “war” narrative as the U.S. hawks hope. In doing so, the forces that counterbalance the U.S. would lose their effectiveness, and we would quickly fall into the trap of a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” easily breaking through the current “foundation” of sanctions. On the contrary, the more strategic composure we exhibit and counter-sanctions with a globalized, market-oriented professional approach, maintaining a competitive yet unbroken stance, the more uncomfortable it will be for the U.S. hawks and the more consistent with China’s long-term semiconductor goals.

Author: ICwise

1. This article is compiled from online sources. If there is any infringement, please contact us for removal.

2. The published content represents the views of the author and not the position of DiskMFR.

3. Related Reading: Unveiling the Restrictions of Japan’s Semiconductor Ban

4. Related Reading: Highlights of A new round of US Semiconductor Export Control

5. Related Reading: US Firms Tempted to Reshore PCB Production Amid Disruptions

6. Related Reading: The Impact of U.S. Sanctions on NVIDIA: A Closer Look